What it is

The NSW Shark Meshing (Bather Protection) Program has operated since 1937 at selected beaches. Shark nets are set offshore from 51 beaches, and checked several times a week during the meshing season. The program aims to reduce the risk of shark interactions by catching and killing large sharks in an attempt to reduce their populations. Whilst the language surrounding the program has evovled over the years, including removal of ant explicit references to culling, the program has fundamentally remained the same.

What this means in practice

-

The Shark Meshing Program is at its core, a shark fishing/culling program, based on the 1930's premise that lower shark populations means safer beaches.

-

Shark nets are not barriers; they are short 150m sections of mesh fishing nets, set parallel to the beach. They do not keep sharks away or create an enclosure of any kind.

-

Shark Nets are by nature not species specific, and catch both target species (white, tiger and bull sharks) and non‑target animals. Over 90% of catch historically is non‑target species.

-

Catches include protected wildlife such as dolphins, turtles, rays and humpback whales - which would be illegal and prosecutable offences - if not for the exemption that is granted to NSW DPI by NSW DCCEEW.

Image credit: Humane World for Animals

How Shark Nets Operate

Operation

-

Nets are installed seasonally at selected beaches.

-

Mesh size and placement are designed to entangle and kill animals.

-

Caught animals may be found alive or deceased at routine inspections. These occur only every 72 hours, leading to high mortality rates.

Important Considerations

-

When animals are caught, odours and distress cues can attract sharks to the area.

-

DPI has not assessed any additional risk created by this side effect of the program for swimmers and surfers.

-

General DPI "Shark Smart"safety advice is to avoid swimming near bait, dead animals, struggling fish, and shark nets.

Effectiveness and Limitations

Fatal shark bites per capita had an all time peak in the 1880s in NSW, and steadily decreased since. There was another spike of fatal shark bites in the 1930s, which again, steadily decreased since.

The introduction of shark nets in the 1930s is often cited as the reason for the reduction in fatal shark bites after the 1930s, however this ignores the same trend from 1880-1920 with no shark nets present. Whilst this simplistic correlation of trends post 1930s may seem like evidence that shark nets work, correlation does not equal causation. Shark nets were fully removed for three years during WWII, and have also been seasonally removed every winter since 1989, and there has been no increase in shark bites during these periods of absence.

Various peer-reviewed scientific analyses, including one co-authored by DPI scientists, indicates there is no clear scientific evidence that reducing local shark numbers through meshing reduces risk at beaches.

The reduction in fatalities since 1937 is instead attributed to other factors such as faster intervention from lifeguards and first responders, faster transport times to hospitals, and improved medical care for severe trauma, since the 1930's. In some regions shark nets may go many years without catching any target sharks resulting in 100% bycatch, meaning that even if the belief is held that catching and killing target sharks is effective, the program is unsuccessful at this.

"We could not detect differences in the interaction rate at netted versus non-netted beaches since the 2000s, partly because of low incidence and high variance. Although shark-human interactions continued to occur at beaches with tagged-shark listening stations, there were no interactions while SMART drumlines and/or drones were deployed."

Drone Sightings inside shark nets

GPS shark surveillance drone sighting data from Randwick Council has been overlayed with the Shark Net position and size at Maroubra to illustrate visually that shark nets do not form a barrier or prevent sharks from entering the surf zone.

Image credit: Envoy Foundation

Environmental Impacts

Nets capture many non‑target and protected species. This killing of protected species is permitted via a 'Joint Management Agreement' (JMA) between DPI and DCCEEW, which provides a legal defence for otherwise protected wildlife deaths. It is the only JMA in the state.

Dolphins & Whales

Entanglement events occur during the meshing season. Animals may be released or recovered deceased.

Turtles & Rays

Several turtle species and large rays are susceptible to entanglement. These species are otherwise protected under NSW and Commonwealth law.

Non‑target Sharks

A high proportion of catch comprises harmless or threatened sharks (e.g. Grey Nurse and Scalloped Hammerheads).

Survival Rates

Released animals are often not tagged or tracked and actual survival rates or post mortality rates are unknown.

Attractant Effect of Shark Nets

Caught or decomposing animals can release odours and produce sounds of struggling prey. These cues are known to attract sharks. DPI holds extensive photographic records of sharks feeding on animals caught in shark nets. There has been no assessment or research on any additional risk this may present to swimmers or surfers near shark net locations.

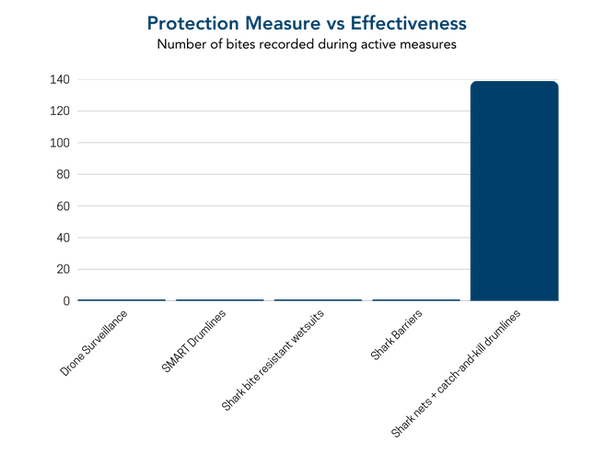

Modern, Non-lethal Measures

NSW and other jurisdictions use additional measures that maintain beach safety without the environmental costs of meshing.

Drone surveillance

Trained pilots monitor nearshore waters and alert lifesavers. No shark bites recorded during active drone surveillance.

SMART drumlines (non‑lethal)

Tagged sharks are relocated offshore. No shark bites recorded during active, non‑lethal use.

Shark barriers

Fixed enclosures for swimming areas. Physical separation with no bycatch; zero recorded bites within barriers.

Personal deterrents

Independently tested electrical deterrents reduce risk for individuals.

The Myth of Territory

One of the central justifications for the NSW Government’s shark net program is that nets supposedly prevent sharks from establishing “territories” near beaches. This claim is prominently featured in SharkSmart NSW materials, but there is no scientific evidence to back it up.

A Claim Without Science

The Department of Primary Industries (DPI) has repeated this claim across various official materials — from their website to public statements. But if you dig into the science (as we did), the evidence doesn’t stack up:

-

2009: The NSW Fisheries Minister at the time described the nets as a “psychological barrier” in Parliament — with no supporting data.

-

2015: The DPI clarified there was no scientific evidence that sharks aggressively defend small, localised territories. Their attempt to redefine “territory” to mean loose aggregations doesn’t hold up scientifically.

-

Senate Inquiry Submission (2017): Multiple experts challenged the claim, citing long-distance tagging data that shows species like great whites and bull sharks are highly mobile — not territorial.

-

Internal DPI documents: Describe territorial prevention as a goal, not a proven outcome.

-

2025: NSW DPI finally admitted that sharks do no establish territories, confirming, without admitting, that their previous statements have been false.

Put simply: shark nets don’t stop sharks from establishing territories, and the concept of shark “territories” around beaches isn’t scientifically grounded to begin with. The 2009 claim in Parliament may have been the origin of these claims, which seem to have been retrospectively created long after the meshing program started, as a way to justify the shark net program.

No Defined Protection Area

Despite operating the program since 1937, DPI does not provide any guidance around key questions related to the effectiveness of nets:

-

What size or shape area around a net is considered “protected”?

-

Is the “protected” zone defined by a radius or straight lines? What are the dimensions?

-

How is a netted beach defined in incident reports, especially when shark bites occur nearby?

Why This Matters

There is no evidence of shark nets stopping sharks from forming territories, and the area of protection (if any) is not defined by DPI. Any claims regarding deterring the establishment of territories, or protection provided by shark nets, is not supported by evidence or research, and should not be made by Government or media.

How to reduce the chances of an encounter with a shark

The below tips are official NSW Government SharkSmart advice on how to reduce your chances of an encounter with a shark.

Swimmers and Surfers

-

Tell an on-duty lifesaver or lifeguard if you see a shark.

-

Stay close to shore when swimming.

-

Stay out of the water with bleeding cuts or wounds.

-

It's best to swim, dive or surf with other people.

-

Avoid swimming and surfing at dawn, dusk and night – sharks can see you but you can’t see them.

-

Keep away from murky, dirty water, and waters with known effluents or sewage.

-

Avoid areas used by recreational or commercial fishers.

-

Avoid areas with signs of bait fish or fish feeding activity; diving seabirds are a good indicator of fish activity.

-

Dolphins do not indicate the absence of sharks; both often feed together on the same food, and sharks are known to eat dolphins.

-

Be aware that sharks may be present between sandbars or near steep drop offs.

-

Steer clear of swimming in canals and swimming or surfing in river/harbour mouths.

-

Avoid having pets in the water with you.

-

Keep away from shark nets and other shark mitigation measures.

-

Consider using a personal deterrent.

Divers, Snorkellers and Spearfishers

-

Understand and respect the environment. Find out which species of shark you are most likely to encounter and what behaviour to expect from them.

-

Realise that diver safety becomes increasingly difficult with decreasing visibility, such as at night or in turbid water and with increasing depth and current.

-

Discuss dive logistics and contingency plans such as hand signals, entry and exit considerations and separation procedures with your dive partner before you enter the water.

-

Be aware that using bait to lure fish may attract sharks.

-

Don't chase, grab, corner, spear or touch a shark.

-

Don't use bait or otherwise attempt to feed a shark while underwater. Feeding may radically change the shark's behaviour and may lure other sharks.

-

Observe and respond to a shark's behaviour. If it appears excited or agitated, exhibiting quick, jerky movements or other erratic behaviour, leave the water as quickly and calmly as possible. Try to minimise splashing and noise.

-

Be aware of the behaviour of fish. If they suddenly dive for cover or appear agitated, leave the water as quickly and calmly as possible. A shark may be nearby.

-

Do not attach speared fish to your body or keep them near you; use a float and line to keep your catch well away.

Frequently asked questions

Evidence and Reports

Hoel & Chin (2020) — Scientific basis for global safety guidelines to reduce shark‑bite risk.

Tester (1963) — Attraction to odours from stressed fish.

Disclaimer:

This website provides factual and transparent information about the NSW Shark Meshing (Bather Protection) Program, including limitations and environmental impacts. It is not the official NSW Government SharkSmart website. It is designed to present information that is often omitted or misrepresented by DPI. For the government site, visit sharksmart.nsw.gov.au.